Cloud and SaaS have become the default place to store and process sensitive data. They have also become the default place to lose it.

Recent years have seen the same pattern repeat: a single weakness in a cloud platform, data-warehouse service, or widely used SaaS component is exploited once, and data for many organisations and millions of users moves at once. File-transfer vulnerabilities, data-warehouse credential campaigns, and third-party SaaS breaches are no longer outliers; they are examples of a structural problem in how multi-tenant systems are built.

This article examines that problem—wholesale compromise of SaaS and cloud platforms—and then outlines an alternative design direction: data-in-use protection with structural sharding of multi-user data. The goal is not to make breaches impossible, but to make it structurally impossible for one compromised user, process, or integration to retrieve everyone else’s data, because it simply does not possess the cryptographic keys required to do so. Mimir’s data-in-use protection model is presented as a concrete instantiation of that idea.

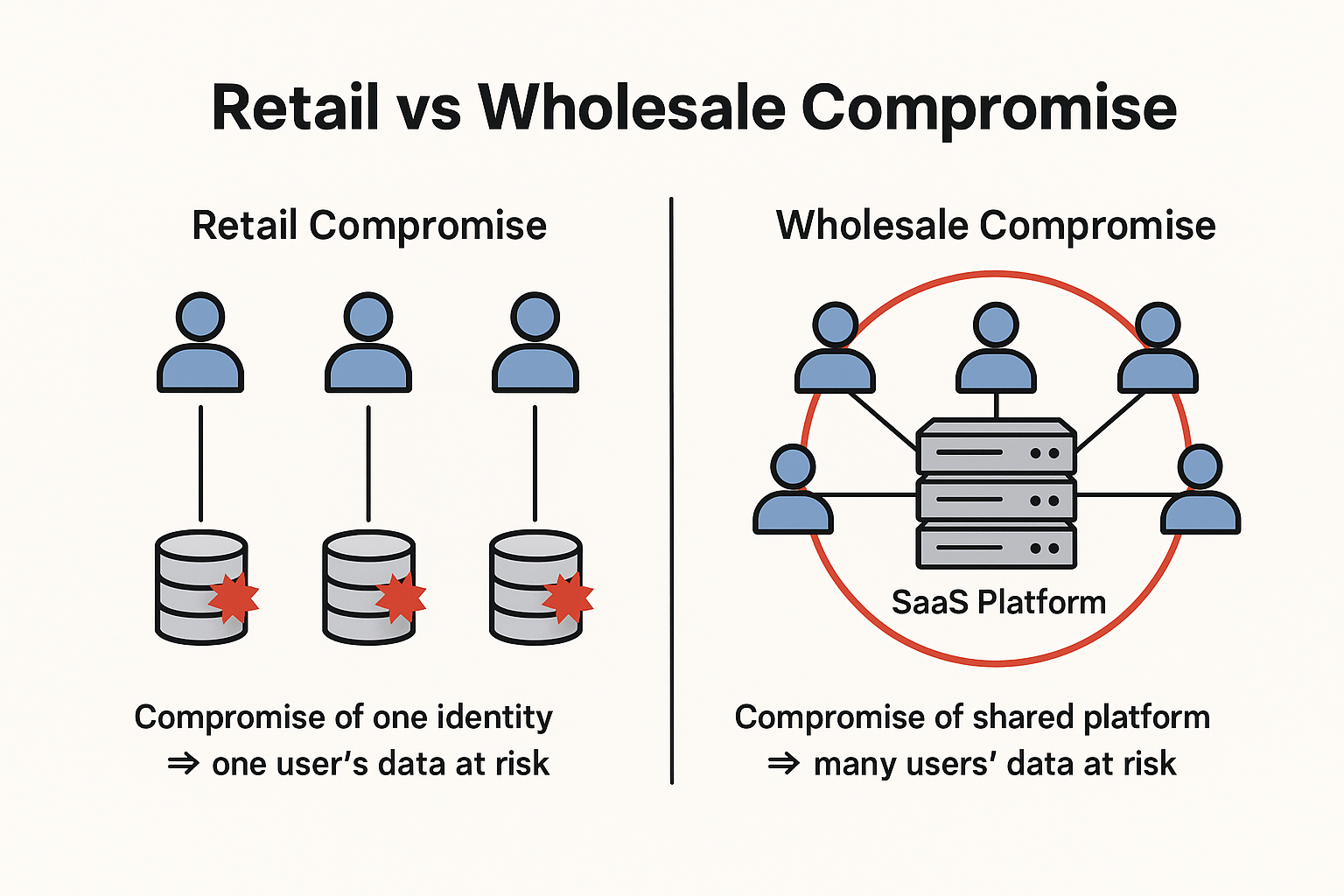

Retail vs Wholesale Compromise

Security teams are accustomed to dealing with what might be called retail compromise: an individual account is phished, a laptop is infected with infostealer malware, or a user approves a malicious MFA prompt. The attacker gains control of a single identity and whatever that identity can legitimately access.

These events matter. They lead to fraud, targeted extortion, and compliance headaches. However, well-designed systems can often limit the blast radius of a single compromised user.

The incidents that drive systemic risk look different. They are wholesale compromises:

- A vulnerability in a shared file-transfer or integration product is exploited across thousands of deployments.

- A set of cloud data-warehouse accounts without multifactor authentication are accessed using harvested credentials, across many different customers.

- A third-party SaaS provider with broad read access to customer data is compromised, affecting most or all of its client base at once.

From the perspective of the victim organisations, the common feature is clear:

One campaign, one exploited weakness, many customers’ data exposed in one motion.

Individual user mistakes and endpoint compromises may be involved, but they are not the main driver of impact. The real driver is how the platform aggregates and exposes data once an attacker is “inside”.

How Wholesale SaaS Breaches Happen

The specific entry vectors vary, but they fall into a handful of recurring classes. Each of them exploits the fact that multi-tenant systems centralise data and centralise trust.

1. Stolen Cloud and SaaS Credentials

Stolen or misused credentials remain the dominant starting point for attacks on web and cloud services. Infostealer malware collects usernames and passwords from browsers and password stores; password reuse and weak MFA policies do the rest.

In a multi-tenant data-warehouse or SaaS platform, one successful login with a powerful account is rarely just “one user’s problem”. If that account is a service user, an administrator, or a role used for analytics or support, it may have the ability to query or export data for large segments of the customer base.

The root issue is not merely weak passwords. It is that a small number of identities are allowed to see a very large portion of the aggregate dataset.

2. Exploited Vulnerabilities in Shared Services

The MOVEit family of incidents illustrated how a single software defect could be weaponised across thousands of organisations using the same product. A previously unknown flaw in a shared file-transfer component allowed an attacker to execute crafted queries and exfiltrate sensitive files.

This was not a targeted attack against one victim at a time. It was a systematic sweep across every reachable instance of the vulnerable software, each of which handled cleartext data for many users.

Again, the core issue is that one piece of infrastructure sits in the cleartext path for many organisations’ data. Exploit that infrastructure, and the attacker inherits that vantage point.

3. Cloud and SaaS Misconfiguration

Cloud storage and SaaS platforms offer rich configuration models. That flexibility is powerful, but it also means that a single misconfiguration—an overly permissive role, a public storage bucket, an integration granted broad read access—can expose large datasets.

If a misconfigured role can list and read multi-tenant tables or shared data lakes, then any compromise of that role (or any component that uses it) becomes a wholesale event by default.

4. Third-Party SaaS and Supply-Chain Compromise

Modern SaaS applications rarely exist in isolation. They are surrounded by observability tools, analytics platforms, ticketing systems, call-centre solutions, and now AI assistants. Many of these are themselves SaaS products, connected via API and often granted wide read access “for convenience”.

When one of these upstream or downstream providers is compromised, the impact extends beyond that vendor. Every customer that allowed it broad access to its own data inherits the consequences.

From the platform operator’s perspective, this can be indistinguishable from a direct breach: the integration had the authority to see everything, so the attacker did too.

The Economics of Blast Radius

Industry studies such as IBM’s Cost of a Data Breach series consistently place the average total cost of a breach in the multi-million-dollar range, with incidents in highly regulated sectors and in the United States often significantly higher. Large-scale, cloud-centred incidents involving tens of millions of records can produce aggregate losses in the billions once direct response, regulatory penalties, customer notification, business interruption, and long-term churn are considered.

For an individual SaaS provider, the key point is not the precise global average, but the shape of the risk:

- A small number of privileged identities, components, and integrations have broad access to multi-tenant datasets.

- A successful attack on any one of these often leads to a platform-wide or sector-wide event, not a single-customer incident.

- The cost of such an event is not linear in the number of users compromised; it escalates due to reputational damage, sector-wide scrutiny, and systemic remediation efforts.

As long as architectures make it easy for one compromise to touch many users at once, this form of tail risk remains.

The Architectural Root Cause

Traditional SaaS security programmes focus on strengthening perimeter defences, hardening identity, encrypting at rest and in transit, and improving detection and response. These are all valuable, but they operate around the core architectural pattern, which largely remains unchanged:

- Centralised plaintext aggregation

Multi-tenant databases, data warehouses, and search indices often hold large volumes of user and tenant data in cleartext at the application layer. Encryption at rest protects against physical media theft, not against legitimate queries or compromised application components. - “See-everything” components

Application servers, background jobs, administrative tools, ETL pipelines, dashboards, customer support consoles, and third-party integrations are routinely granted extensive read access. They are designed to traverse boundaries for convenience: one process can read many users’ records, across many tenants, in one operation. - Lack of boundaries in data-in-use

Once data is decrypted for use—inside processes, caches, query engines, and log streams—there is usually no further cryptographic segmentation. Any component authorised to run a query or retrieve an object can, in principle, see all records that query can reach.

In this discussion it is reasonable to set aside the extreme case of a fully compromised endpoint where an attacker can already act precisely as a given user. If an adversary has that level of control, they can usually obtain that user’s data through legitimate means. The more interesting question, from a platform perspective, is this:

Given that some accounts, components, or integrations will eventually be compromised, how much data does each of them need to be able to see by design?

At present, the answer in many SaaS architectures is effectively “almost everything”.

Design Goals for Blast-Radius-Aware Data-in-Use Protection

To improve on this, design goals must move beyond preventing intrusion and towards constraining what any successful intrusion can access. For multi-tenant SaaS, that suggests at least four requirements.

1. Decryption Must Be Local, Narrow, and Session-Bound

Decryption of sensitive data should occur:

- Only for a specific tenant, user, or tightly scoped workflow.

- Only within an active, validated session or operation.

- Only in a confined environment, with plaintext discarded immediately after use.

There should be no long-lived, server-side component that holds a global view of all tenants’ data in cleartext.

2. Keys Must Be Segmented and Decoupled from Shared Infrastructure

Instead of a small set of keys capable of decrypting entire databases, architectures should adopt:

- Per-tenant and per-principal key hierarchies, where each tenant and, within that tenant, each user or role has its own cryptographic domain.

- Key management and storage that are logically or physically separated from the main application and data tiers.

Compromising a shared database or an application process must not automatically grant access to the keys needed to decrypt other tenants’ or other users’ data.

3. Servers Should See Ciphertext by Default

Wherever practical, shared infrastructure—databases, object storage, internal queues—should store and handle opaque ciphertext packages and structurally non-sensitive identifiers (for example, random package IDs), not raw personal or business data.

Under this model:

- The server routes and persists encrypted “data packages” based on identifiers.

- Operational logic in the multi-tenant layer deals with addressing, versioning, and policy decisions, not with cleartext content.

- Decryption is performed only in narrowly scoped components operating on behalf of a specific tenant or user.

This does not eliminate all risk, but it removes the historic pattern where “one query against the right table” can reveal everything.

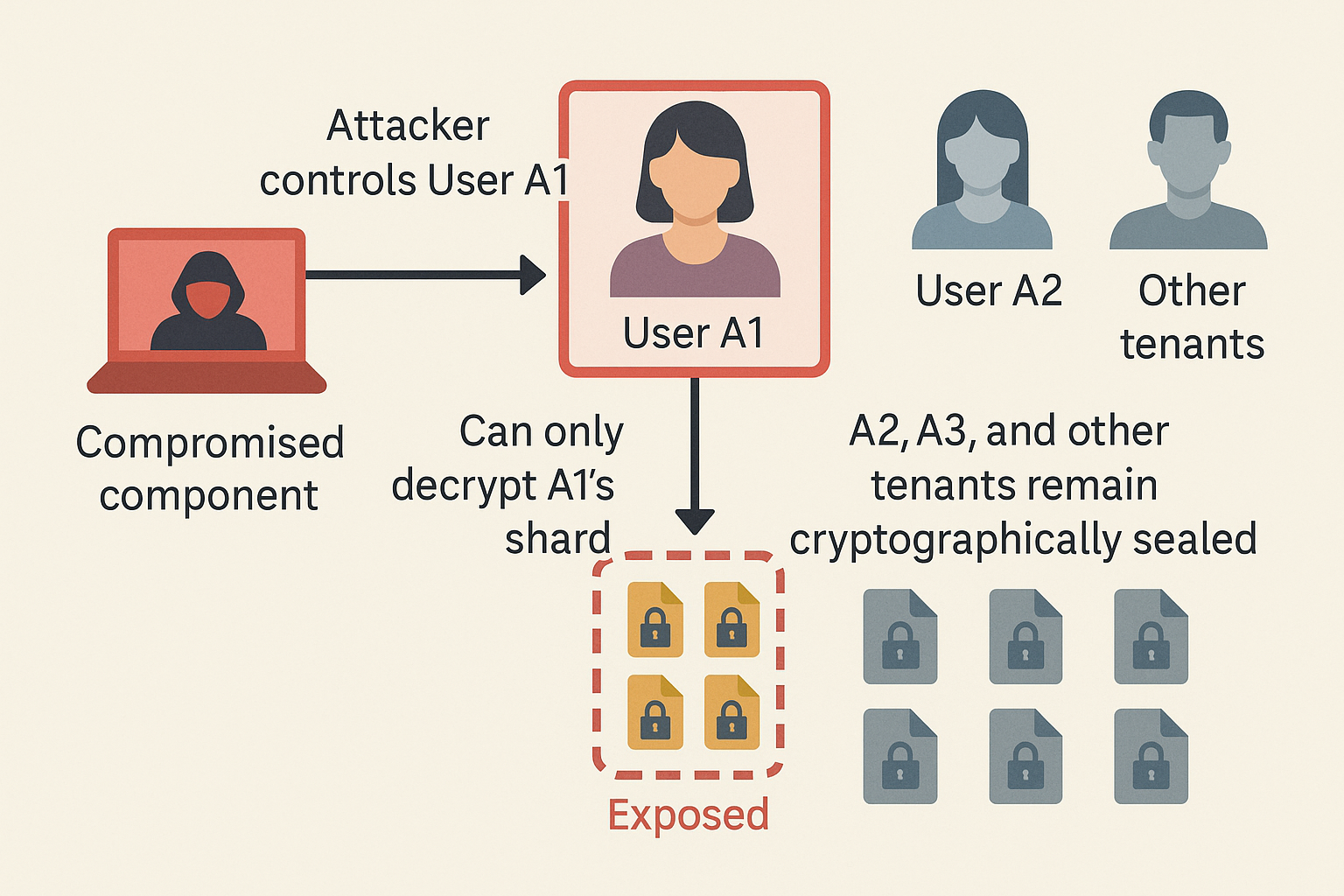

4. Structural Sharding Along Access Lines

A further step is to shard data along the same lines as access control, and to enforce that sharding cryptographically.

Concretely:

- Data belonging to different tenants is encrypted under different keys, so that a compromise in Tenant A cannot decrypt Tenant B’s packages.

- Within a tenant, data for different users or roles is encrypted in separate cryptographic domains, so that even if an attacker fully impersonates one user or compromises a component acting on that user’s behalf, it does not possess the keys needed to decrypt other users’ data.

- Shared infrastructure never sees keys spanning multiple shards; it mediates traffic but cannot, on its own, assemble a cross-user or cross-tenant view.

This is what is meant by structural sharding of multi-user data along access lines: the cryptographic boundaries in the storage model match the logical boundaries in the authorisation model. The structure of the system itself enforces that a user—or anything acting with that user’s keys—cannot retrieve data that belongs to someone else.

Mimir’s Data-in-Use Protection Model

Mimir’s technology is designed around precisely these principles. At a high level, it implements data-in-use protection, structural sharding, and key segregation in a way that can be integrated with existing SaaS architectures.

1. Package-Centric, Encrypted Storage

Sensitive records and files are not stored as mutable rows in a single multi-tenant table. Instead, Mimir organises them into individually encrypted and signed packages. Each package:

- Is bound to a specific tenant and, optionally, to a specific user or access domain within that tenant.

- Is addressed by non-sensitive identifiers (such as random or content-derived IDs); the platform does not need business or personal metadata in the clear to route or store the package.

The multi-tenant server tier and underlying storage see only these opaque encrypted packages and their non-sensitive identifiers, never the plaintext content.

2. Client-Side and Edge-Side Cryptography

Encryption and signing are performed as close as possible to where data originates—often in a client-side runtime (for example, WebAssembly in the browser) or a narrowly scoped edge service.

The multi-tenant application and persistence layers:

- Receive already encrypted packages for storage.

- Return encrypted packages for use.

- Do not need access to plaintext at any point to perform routing, versioning, or policy enforcement.

Plaintext exists only in the confined client or edge environment that is acting on behalf of a specific tenant or user.

3. Per-Tenant and Per-User Key Domains

Mimir maintains separate key domains:

- At the tenant level, so that each customer’s data is cryptographically isolated from other customers’ data.

- Within a tenant, along user or role boundaries, so that each user (or tightly defined user group) has its own encryption context.

The keys for these domains are not stored alongside the data and are not exposed to generic server processes. A user, or an application acting on behalf of that user, can only decrypt packages for which it holds the appropriate keys. The absence of other keys is not a policy decision; it is a structural fact.

This is the practical expression of structural sharding: even inside a single tenant, one user’s key material is insufficient to unlock another user’s data, and a compromised process operating on behalf of that user is equally constrained.

4. Session-Bound Data-in-Use

Mimir couples decryption to active sessions and explicit operations:

- When a user or workflow needs to read data, the relevant keys are used—within the client-side or edge runtime—to decrypt only the required packages.

- Plaintext exists only in that confined environment for the duration of the operation and is then discarded.

- The multi-tenant server tier always persists only opaque ciphertext packages addressed by non-sensitive identifiers; its view of the data does not change with session state.

This aligns with a pragmatic threat model: if an endpoint or user account is completely compromised, the attacker may still access that user’s data, but cannot escalate to a full-database or full-tenant view, because the keys to do so are simply not present.

5. Limiting Blast Radius by Construction

Under this model, many traditional wholesale attack paths are disrupted:

- Compromising the multi-tenant datastore yields encrypted packages, not directly exploitable records.

- Compromising a powerful but generic integration that never sees keys does not grant access to cleartext.

- Compromising one user’s device or access token does not provide the keys required to decrypt other users’ data, even within the same tenant.

The system is engineered so that failures are narrow and local rather than broad and systemic. Breaches may still occur, but they resemble retail compromise rather than wholesale compromise.

Where This Leads

For SaaS providers, the lesson of recent years is that the default architecture—large centralised plaintext stores protected by perimeter controls and monitoring—is no longer sufficient. As long as one compromise can expose many customers’ data at once, the economic and operational risks remain uncomfortably high.

Data-in-use protection, combined with structural sharding of multi-user data along access lines, offers a different path:

- Servers and shared infrastructure operate primarily on ciphertext and non-sensitive identifiers.

- Keys are segmented by tenant and by user, and kept out of the shared blast radius.

- A user, or a process acting with that user’s authority, cannot decrypt other users’ data because it does not hold the necessary keys.

Mimir’s technology is one example of how to realise this in practice, without discarding the flexibility and scale that make SaaS attractive in the first place.

Subsequent articles can delve into concrete reference architectures, integration patterns with common cloud stacks, and quantitative analysis of how much blast-radius reduction can be achieved. The strategic point, however, is already clear: re-architecting data-in-use and key management is now as important as strengthening perimeters, if we wish to turn catastrophic wholesale failures back into manageable, localized events.